What are knowledge specialists, and why do they matter?

Expertise is everywhere. In different cultures and across historical time, people have dedicated their lives to becoming exceptional physicians, philosophers, mathematicians, theologians, painters, designers, leaders, athletes, and musicians (among many other things).

But expertise incurs costly investments of time, effort, and possibly financial resources. A PhD, for example, typically takes several years of training after completing an undergraduate degree – that’s extra coursework, but also teaching responsibilities and a full-time research job (which may include fieldwork in certain disciplines). Even without credentials, and even with a natural advantage in skill, expertise takes a ton of deliberate practice. There’s simply no way to get around it: expertise is a huge investment.

So why is expertise such a deeply human, frequently recurring feature of human societies? Why do humans often spend so much time specializing in knowing a lot about really specific things?

Expertise as knowledge specialization

A tempting response to this question may be that people enjoy learning. While this is true, it misses an opportunity to explain why our minds evolved to enjoy learning so much in the first place. Compared to our closest primate relatives, humans have really long childhoods that we use to gain a lot of practical knowledge before adulthood. Most people can make a pretty decent living without investing in expertise as adults, but we still see experts everywhere dedicating their lives to perfecting their crafts – time that could have been spent in other ways.

A recent paper that I wrote with Cynthiann Heckelsmiller and Ed Hagen explores this tendency from an evolutionary and cross-cultural perspective. If you pick up an ethnography about almost any society, there’s a good chance you will find some kind of description of a specialist whose role is to knowing a lot more than most others about a specific topic, such as plant taxonomies, genealogical histories, or medical ailments. We started referring to these individual experts as knowledge specialists.

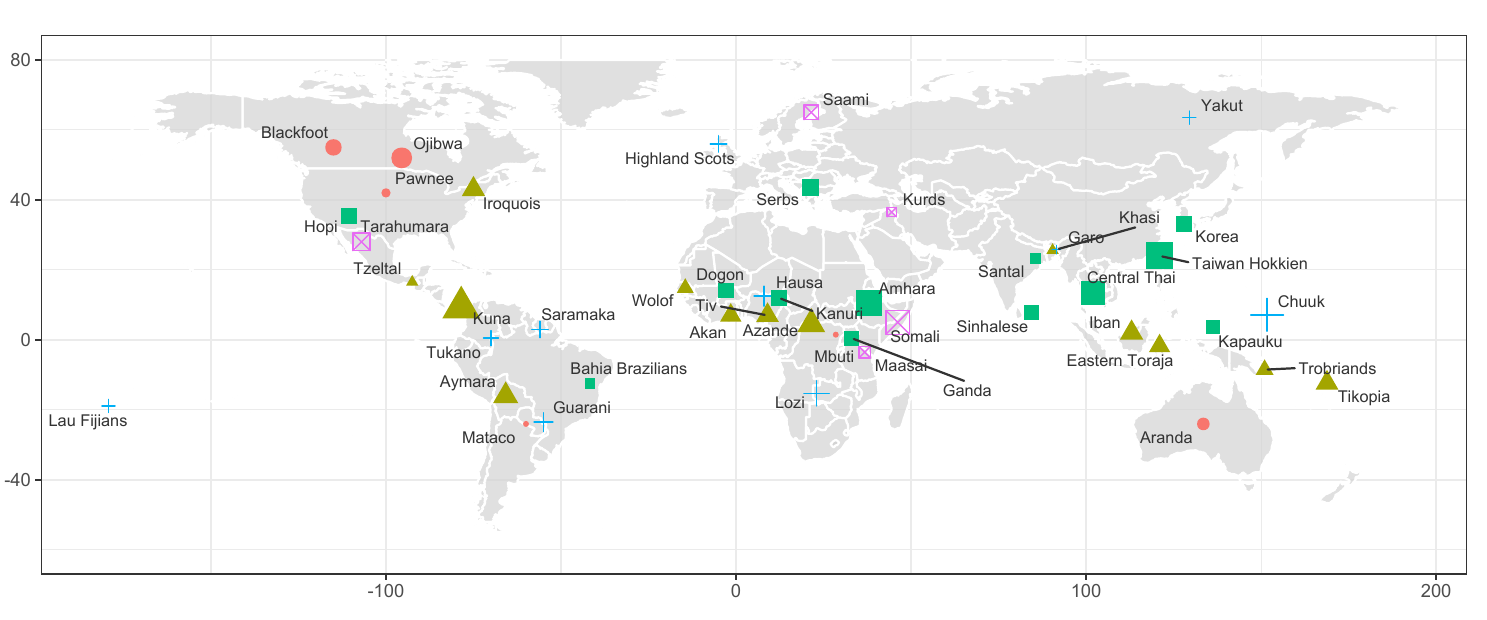

To glean insights about these knowledge specialists, we analyzed a lot of descriptions about them from around the world. What kinds of patterns would emerge from the data? To gather our descriptions, we searched through ethnographies about 55 traditional societies in the electronic Human Relations Area Files, the locations of which are shown on this map.

Knowledge specialists frequently had expertise in areas like botany, medicine, or human behavior. Medicinal specialists were especially common, but we also found a lot of examples of people who focus on things like farming and foraging. Plant knowledge was a common theme across different types of specialists, which makes sense; medicinal specialists need to know herbal remedies, and farmers and foragers need to know edible plants. We found a lot of other areas of expertise too, like canoe-making (another plant topic, since wood is involved) and astronomy.

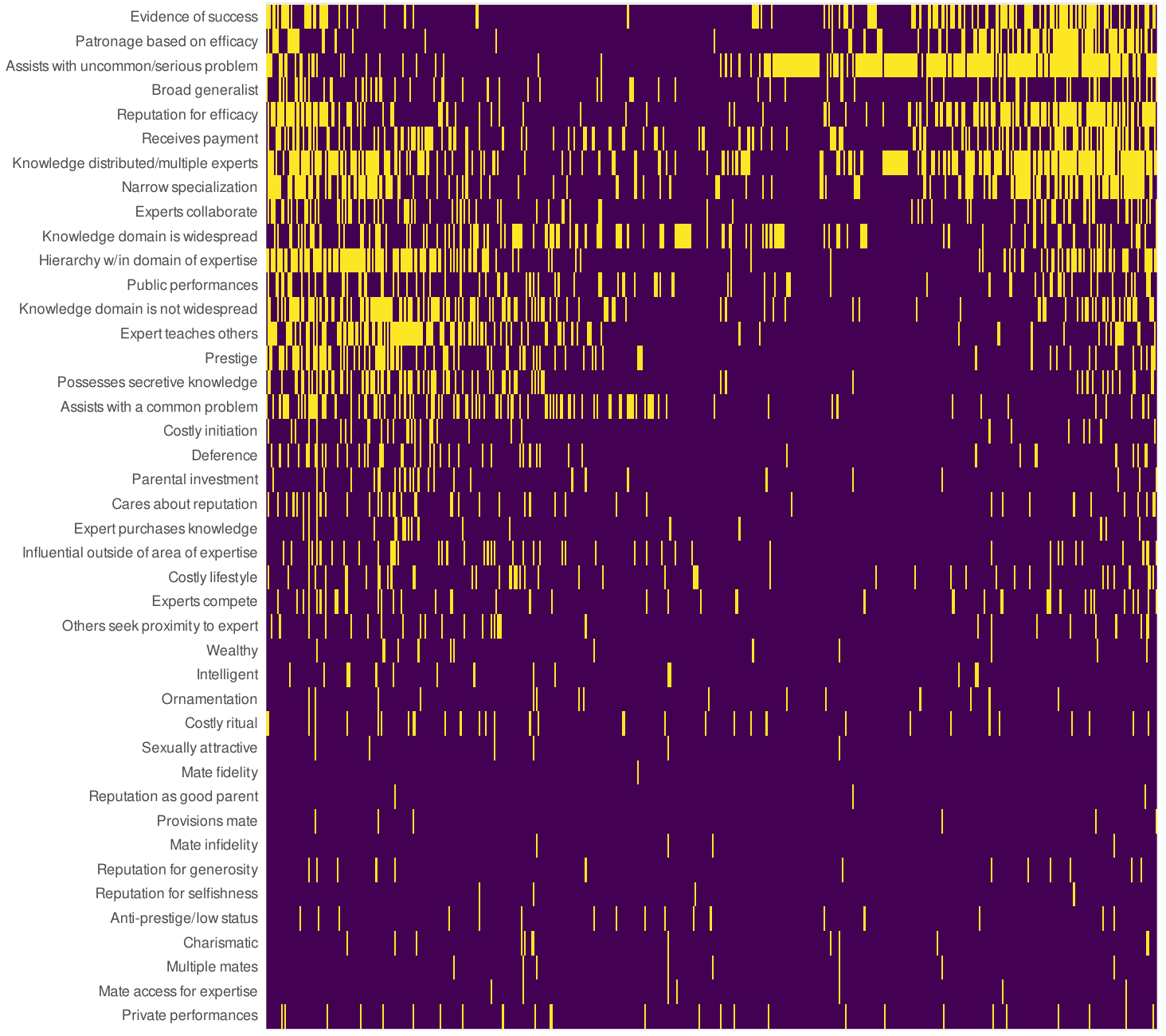

Reading through these descriptions, we recorded whether or not certain features were present. By “features,” I mean things like: Were specialists prestigious? Were they paid for their expertise? Were they secretive about their ideas? Did they have apprenticeships? (And so on.)

We did this for dozens of different features with a total of 547 different descriptions. The heatmap below visualizes our resulting dataset: Each row shows a feature that we looked for, and each tiny column shows a single description. Each feature in each description is either present (the light cells) or absent (the dark cells).

Notice that most of the features are usually absent. That’s pretty standard for this type of study, and reflects an important caveat about it: Since the data are limited to what the ethnographers decided to write down (which might not have matched what we were looking for), we shouldn’t interpret our absences of evidence as evidence of absence. Nevertheless, we can gain a lot of insights from what we did find present in these descriptions.

Making sense of these knowledge specialists

Sometimes specialists were described as helpful and generous members of a community, and other times they were fulfilling a formal role for a clientele who paid them. Sometimes they’d be influential and well-respected, and sometimes they’d be outcasts who are feared by most of society. How can we make sense of all of these apparent themes in the data?

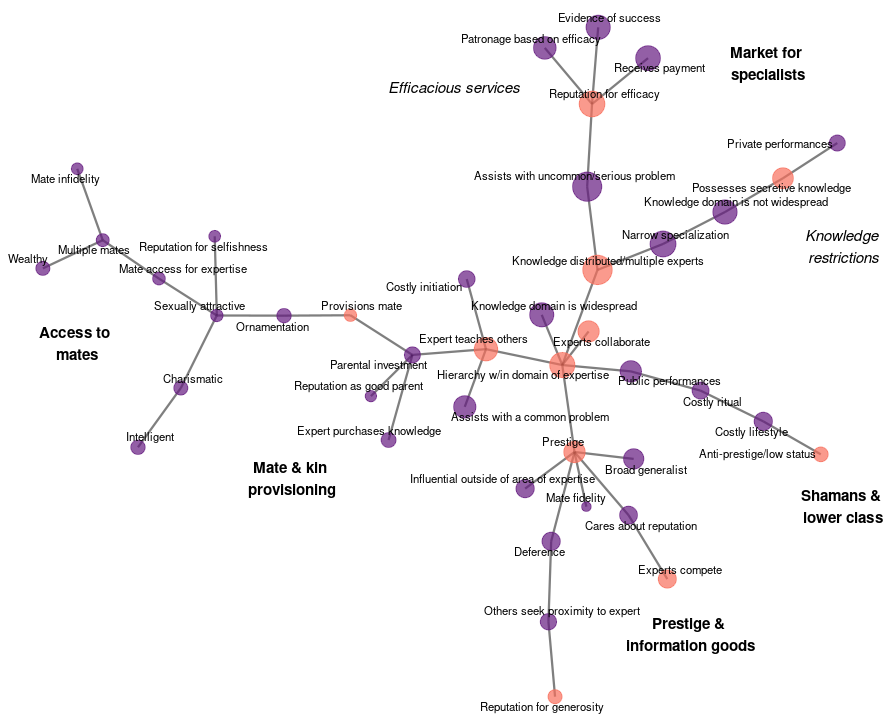

To systematically organize our findings, we created a minimum spanning tree from the big matrix of presence/absence data (in the heatmap above). This basically meant taking all of the possible pairs of features that were either present or absent in each description, and asking which pairs were “closest together” (meaning they frequently showed up in the same descriptions). We might expect generosity and trustworthiness to be close, for example, but we wouldn’t expect either of these to be close to a reputation for selfishness.

Converting these “distances” into a data-driven taxonomy helped us get a sense of the structure in our data. The taxonomy, shown here, essentially maps our features in a way that links the closest ones together. (The node size for each feature indicates how often it was present in the data.)

Our data-driven taxonomy tells us what types of knowledge specialists frequently emerged from our cross-cultural descriptions. Many specialists, for example, were prestigious mentors who were described as generous and trustworthy. Many others, though, provided paid services to a clientele based on restricted knowledge – rare, valuable know-how that specialists would monopolize, often as a secret that’s restricted to a family or guild.

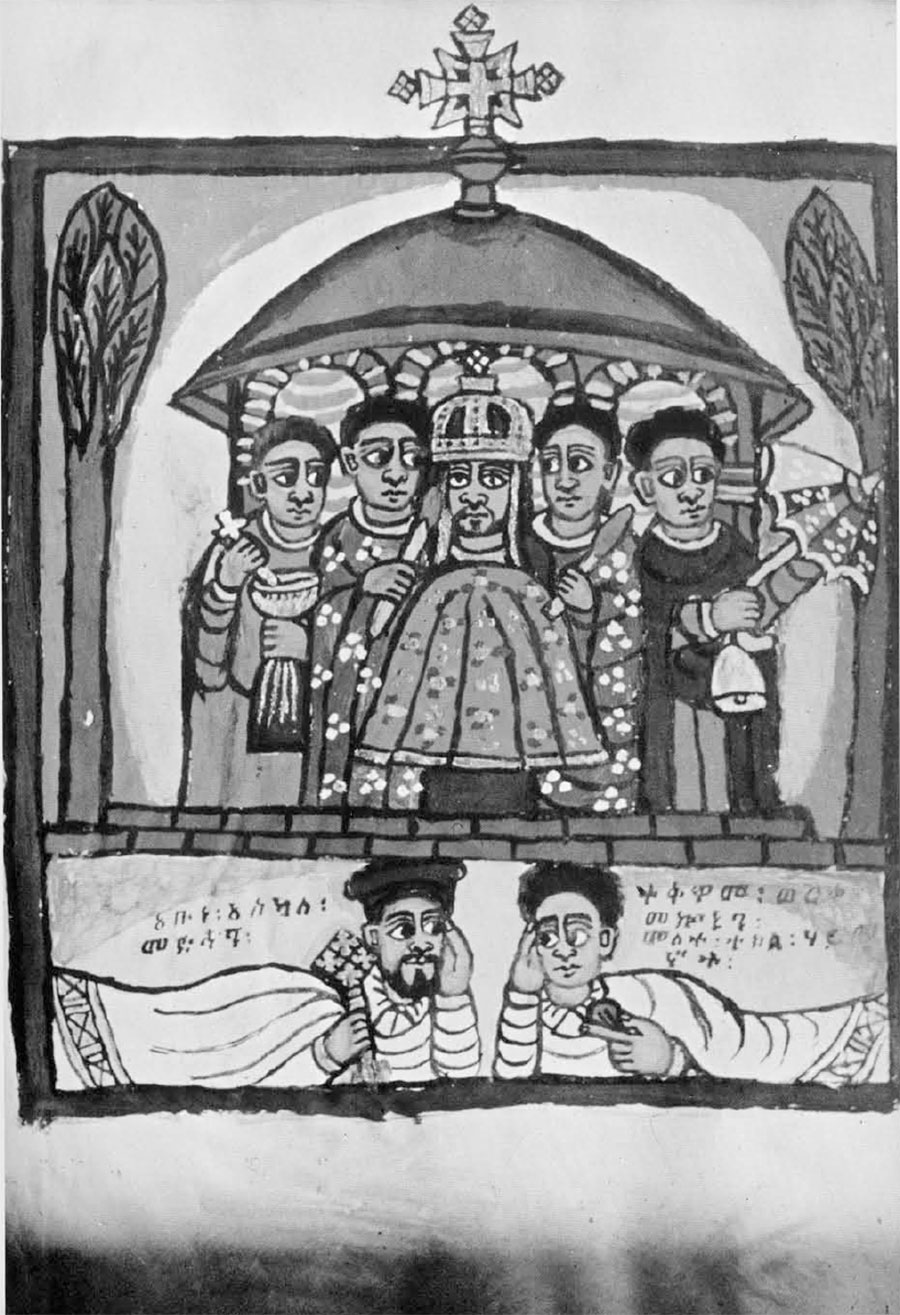

We see a great example of restricted knowledge with the Amharic debtera, a healer with ties to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. As the ethnographer Allan Young puts it, the debtera treats knowledge as a valuable resource. They “control the distribution of this resource among themselves and prevent it from evaporating beyond their ranks,” and their monopoly is possible “because [their] market is closed to laymen.” The closed ranks of the esoteric debtera are also depicted in Amharic art like the image below: Clerics and priests stand visibly before the church building, but the debtera are hidden underneath it.

Interestingly, although the debtera’s healing expertise “includes both technical information and the secret of its sources,” he also invokes magic when he diagnoses and cures ailments. As Young points out, though, the debtera’s magic is not a replacement for knowing how to effectively cure people’s ailments:

[A] debtera never substitutes sham magic for efficacious works. Thus, after the sham magic […] is performed, the client is made to drink an herbal purge which, the debtera tells him, removes the partially digested organs which the magically expelled agent left in the sick man’s body.

We can only speculate about why magic and medicine go together so often among different societies, and I have another paper that does a deeper dive into why this might be the case.

But there are two closely related findings I want to emphasize here. The first point is that we saw many descriptions where, like the debtera, specialists monopolize their services by restricting access to knowledge. We see this a lot when clients outsource some kind of problem (like illness or conflict resolution) to a specialist who “owns” the right expertise for solving it. The value of a specialist’s expertise is based on scarcity (why pay a specialist to solve a problem if I can solve it myself?), creating an incentive for specialists to restrict access to their insights – perhaps by keeping them a secret or by insisting that they’re only shared through a costly apprenticeship. We refer to this scenario, where knowledge is a controlled and valuable resource, as a market for specialists.

The second point, which I want to expand on next, is that these knowledge restrictions are especially common among medicinal specialists – people who help with problems whose causes are unobservable and mysterious.

Medicinal specialists: Is culture all about copying?

Before we see why this second point matters, let’s revisit to our starting question: How do we explain why some people become knowledge specialists with a lot of expertise in a specific topic?

In the evolutionary social sciences, a popular idea suggests that there’s a particular type of exchange between competent experts and aspiring experts. Competent experts gain prestige for their skill, and aspiring experts use prestige as a reliable indicator of whose behaviors they should copy. If your canoe-making skill earns you prestige, for example, then I can prefer to observe and practice your technique. This exchange is a win-win: your expertise is rewarded with prestige, and I gain a useful skill from someone who likely knows what they’re doing.

Although humans might owe a lot of their evolutionary success to their tendency to copy each other’s behavior, not all types of knowledge are so easy to reverse engineer.

Consider the techniques that physicians use to diagnose an illness and judge its possible treatments. Compared to the largely observable techniques of a canoe-maker, physicians rely on a lot of unobservable mental operations like symptom recognition and abductive inference. These are based on intuition and theory, which seem a lot harder to copy.

As we hypothesize in our paper, this might be why we see a different kind of exchange between medicinal specialists and their clientele. If a healer has a lucrative gig helping clients when they’re sick, she’d have an easier time monopolizing that service compared to, say, a canoe-maker (or a cook or a woodworker), whose techniques I could try to observe, copy, and practice.

The key difference here is whether or not an area of expertise includes a lot of observable information about the underlying skill. Medicinal specialists use a lot of rich, unobservable inferences, and even if I tried to figure out their techniques, I’d have a hard time doing so without their helpful instruction. If a specialist in this position doesn’t want to share her secrets, she could easily decline, or perhaps even suggest that it’s magic.

Concluding thoughts

So why do people everywhere invest in expertise? Well, like many of the other universal aspects of human life, it depends. The costly investments of time and effort that specialists put into their expertise tend to yield some kind of benefit – whether it’s prestige or material payments – and those benefits often arise in a context of exchange with students or clients. The context of exchange, though, is shaped by what type of knowledge we’re talking about, along with how scarce and useful it might be for the rest of the community.

This way of framing knowledge as a valuable resource highlights how our tendency to cooperate with each other in mutually beneficial ways going far beyond material resources. Human societies create meaningful “cognitive” worlds for themselves, and knowledge specialists are an important part of these worlds. We rely on them to learn new skills, or to at least benefit from the services that they’re in a position to offer.

If you want to read more about the original study, check out the open access paper here in Evolutionary Human Sciences.

I also posted the data and code from our study to my Github page, and if you’re interested in a short talk I gave about it (during the virtual conference times of 2020), you can check out my presentation on the Open Science Framework website.